Some of the world’s most influential technology relies on simple ideas applied at scale. Think of Netflix: movie recommendations for millions. Or think of Tesla autopilot: cars that tech themselves. Both systems— movie recommendations and autopilot— rely on algorithms that learn from a ginormous data source. A movie review or camera feed may not be informative, but millions of recommendations and video feeds can create magical results.

But how? How can we learn from data that may not fit on a single computer? How can we tweak millions of parameters and expect any sort of improvement?

This idea of machine learning at scale is the focus of a course I’m taking at Carnegie Mellon. For a recent homework problem, we examined grid search, a technique for selecting the best algorithm settings from a range of options. Once you get past some of the math jargon, the solution involves nothing more than a dash of insight and some simple algebra.

Epsilon Coverage Problem Statement

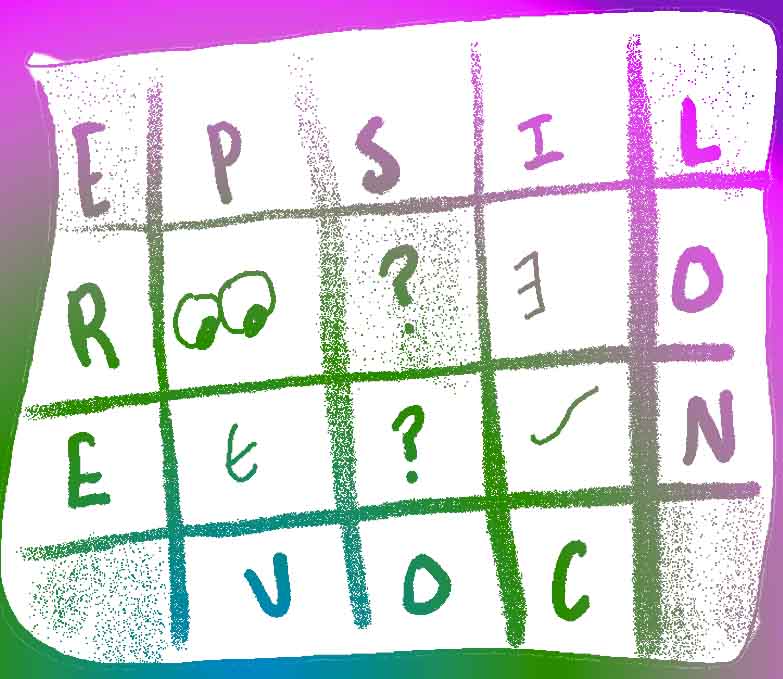

We define the ϵ-cover of a search space S as a subset E⊂S: [E={x∈Rn ∣ ∀y∈S,∃x s.t. ∥y−x∥_∞≤ϵ}]

In words, every coordinate of every point in our search space S is within ϵ of a point in our set E. The ϵ-covering number is the size of the smallest such set that provides an ϵ-cover of S. [N(ϵ,S)=minE{∣E∣:E is an ϵ-cover of S}]

Let's work through a concrete example to make the concept clearer: let's say we want to tune the learning rate for gradient descent on a logistic regression model by considering learning rates in the range of [1,2]. We want to have ϵ=.05-coverage of our search space S=[1,2]. Then E={1.05,1.15,125,1.35,1.45,1.55,1.65,1.75,1.85,1.95}.

We see that any point in [1,2] is within 0.05 of a point in E. So E provides ϵ-coverage of S. The ϵ-covering number is 10. The questions below will ask you to generalize this idea.

Problem Statement [Translation]

That’s a whole bunch of jargon. A simplified (and silly) problem statement would read something like this: We’re standing at a random point in some multi-dimensional space. We need to poop. We want to be at most a distance ε from the nearest restroom.

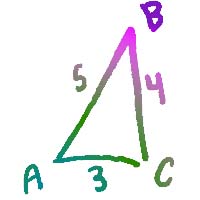

Note, that the distance metric here is a little different than normal. Here, the distance metric is the L-infinity norm which is defined as, “the absolute value of the largest component of the vector.” So, for the triangle shown below, the L-infinity norm from A to B is 4.

| Example Triangle |

|---|

|

| The L-infinity norm is different than the standard diagonal distance from A to B. |

Question One

Find the size of a set needed to provide ϵ-coverage (ϵ-covering number) of S=[0,1]×[0,2], the Cartesian product of two intervals. Note that we want this to hold for a generic ϵ

Question One [Translation]

We are standing in a rectangular field that is one mile long and two miles wide. What is the minimum number of restaurants needed so that we are no further than ε from the nearest restroom?

Question Two

Find the ϵ-covering number of S=[a1,b1]×…×[ad,bd], the Cartesian product of d arbitrary closed intervals. Specifically, write down an expression N(ϵ,S) as a function of ai, bi, and ϵ.

Question Two [Translation]

Imagine you are living in some absurd space of arbitrary dimensions. You still need to poop. You still want to be no further than ε from the nearest restroom. How many restrooms are needed in this arbitrary-dimensional space?

Tips

- Draw a picture. Get a feel for the space and geometry of the problem. Pictures are easier to consider than abstract problem statements.

- Start simple. Before considering 4D hypercubes think about a 1D line.

- Find a pattern. Can you find a solution in the most simple case? If so, slightly increase the complexity and try to identify a pattern.

Answers

Think about it! Don’t worry if you’re still searching for answers thirty minutes in. Take a break. Go for a walk. Don’t stress, there are no points on the line.

But whatever you do, give yourself a chance to discover the solution. Don’t quit before the miracle happens. You got this!

If you have a solution, feel free to message me.

Bonus Problem Statement

There are two basic strategies commonly employed in hyperparameter search: grid search and random search. Grid search is defined as choosing an independent set of values to try for each hyperparameter and the configurations are the Cartesian product of these sets. Random search chooses a random value for each hyperparameter at each configuration.

Imagine we are in the (extreme) case where we have d hyperparameters all in the range [0,1], but only one (h1 ) of them has any impact on the model, while the rest have no effect on model performance. For simplicity, assume that for a fixed value of h1 that our training procedure will return the exact same trained model regardless of the values of the other hyperparameters.

I won’t bother with a translation, since this problem statement doesn’t have any fancy math jargon. Plus, you’re here for a challenge: embrace the unfamiliar.

Bonus Question

Imagine we are trying to explore as many different hyperparameter configurations as possible. Should we use grid search or random search?